If I didn't have my job, I would envy me. Videogame writers get to help create worlds. Unlike film, where breaking physics requires a massive CGI budget, videogames define their own worlds. Sure, a physics engine like Unreal 4 makes working within a naturalistic world much easier. With just a little coding, objects have weight and will fall; light bounces off surfaces. But it's just as easy to make an island floating over an abyss as a city park. Or a game like Monument, which uses Escher's rules for gravity, and you may be waving hello to the princess walking on your ceiling.

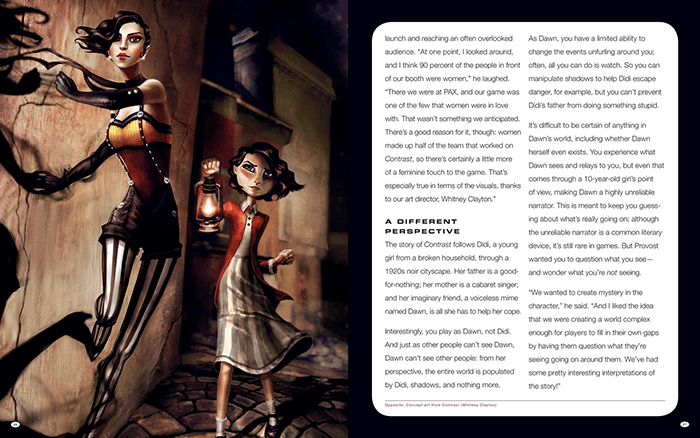

Matt Sainsbury's Game Art is full of worlds, from the original paintings that defined the pop-up world of Tengami, to Whitney's hallucinatory paintings for Contrast, to Demon Hunter, Lollipop Chainsaw, Final Fantasy XIV, and so on -- forty games, forty visions.

Obviously, it is a beautiful book. It is also a series of interviews with game creators, like Guillaume, and Mike Laidlaw, creative director of the Dragon Age franchise. (Dragon Age has some pretty nifty art, eh.) It would probably be worth reading even without the pictures.

So hey, check it out. Oh and -- readers of this blog can get a 30% discount! Go the No Starch Press site and use "COMPLICATIONSENSUE" at checkout...

It would be truer to say, though, that as a video game writer, what I do is explain worlds. When I came aboard Contrast, the game world already existed. My job was to tell the story of why you're in this carnival world of shadows, and figure out who Didi was, and what her relationship with Dawn was.

Likewise, when I started working on We Happy Few, there was already a quaint English town out of Hot Fuzz, and we already had our weedy hero. When I came on board Stories: The Path of Destinies (I think that's what we're calling it now), we already had a fox for a hero, and a mad-looking rabbit. I had to figure out what his name was, and come up with stories for him to inhabit.

So from my experience, game worlds start as art. We Happy Few began as a collaboration between Guillaume Provost, our studio head, and Whitney Clayton, our art director. "What do you want to draw?" asked Guillaume, and Whitney wanted to draw Mod England. Everything flowed from there, and from a few axioms that Guillaume had for gameplay.

Game worlds first come to life in game art. Until then, they're ideas about gameplay (or possibly actual greyboxed gameplay mechanics) in a place that probably isn't special yet.

Matt Sainsbury's Game Art is full of worlds, from the original paintings that defined the pop-up world of Tengami, to Whitney's hallucinatory paintings for Contrast, to Demon Hunter, Lollipop Chainsaw, Final Fantasy XIV, and so on -- forty games, forty visions.

Obviously, it is a beautiful book. It is also a series of interviews with game creators, like Guillaume, and Mike Laidlaw, creative director of the Dragon Age franchise. (Dragon Age has some pretty nifty art, eh.) It would probably be worth reading even without the pictures.

So hey, check it out. Oh and -- readers of this blog can get a 30% discount! Go the No Starch Press site and use "COMPLICATIONSENSUE" at checkout...

No comments:

Post a Comment