Alex: In a narrative game, the main character can be a distinct character with a voice and a past, or a blank slate. How is the player experience different between the two story modes? In the case of a distinct character, is it important to make sure that the player always has their own reason to do what the player character wants to do? How do you make sure of that?

Jon: I’ve got very little interest in blank characters for the player to project onto; I find it makes for very disposable storytelling. (We did it for Sorcery! and it worked out ok, I think, but it does reduce every encounter to “let’s meet another funny local!”) For me, character comes first and story comes second - I think people are interested in human beings, and what those humans do is only a vehicle for letting us spend time with them. (The plot of the Avengers movies are irrelevant, right? We’re there for the banter.)

I also don’t worry very much about the player wanting to do what the protagonist wants to do: it just doesn’t seem to be a problem in my experience. The player, picking up a game, wants to be told what they’re supposed to be doing, because they want to play the game “correctly”.

From there it’s a question of - does the game reward the player for joining in? Does the story surprise and delight you? Do you warm to the characters and want to spend time with them? I have a feeling most people who got into Assassin’s Creed Odyssey did so because they liked Cassandra’s arms; people who got into Outer Wilds enjoyed piecing together its back-story, but in neither of those games does the protagonist’s motivation really matter. There’s enough to keep the game ticking over, and we’re enjoying the ride.

For me the most appealing things about a distinct character are - what is being with this character going to allow me to do? - and I can’t wait to see how this character going is to react to what’s coming next!

Alex: What are the different needs of dialog to be delivered as text on the screen, and dialog intended to be performed and recorded?

Jon: Oddly enough, I’ve got very little experience of recorded dialogue! Almost all the work I’ve done is either prose, or “graphic novel”-style dialogue bubbles, and I suspect all three are different in terms of their pacing and delivery. I generally think a lot about pace and length: our prose games try to be very snappy; ideally every paragraph has a joke or a moment of insight. And I’ve really enjoyed writing “paced dialogue” of Pendragon and Heaven’s Vault, where each dialogue line has to be short, but the way they stack together of chain can deliver some nice effects.

I’d love to work with actors more, though; as a writer it’s a delight to have moments really brought to life. I’d just need them to patient with me while I work out what you can and can't actually *say.*

Alex: I think the key thing is never give an actor a result if you can avoid it — no “say the line faster.” Give them an organic reason to give the result — “Okay, you’ve just noticed that the house is a little bit on fire.”

John Badham has an excellent book about directing actors called I’ll Be In My Trailer.

Jon: I did a day’s work on the film set of the movie The Imitation Game as a mathematics consultant, where I worked with Benedict Cumberbatch and Kiera Knightley teaching them some maths for a scene. It’s blink-or-you-miss-in in the final film, but what was really interesting for me was watching a professional actor trying to absorb “how a mathematician talks” as fast and as efficiently as possible.

Alex: What is your favorite narrative delivery victory? What is a narrative delivery system you weren’t able to implement, what were you trying to do, why didn’t it work, and what were you able to do?

Jon: Wow, that’s a hard question. We’ve done some things that have been lovely and emotional and I’m super proud of - I adore the death of Fogg in 80 Days [Fogg can die??? OMG]; I like the romance between Flanker and the protagonist in Sorcery!; I love Aamir the ten year old space pirate in Heaven’s Vault.

But my absolute favourite beat is either the moment in Sorcery! where you - the classic nameless D&D protaganist - confront the mind-meddling Archmage after four long episodes, and he convinces you that your whole journey has been a brainwashed set-up because, after all, you don’t even know your name.

Or else it’s the bit in 80 Days where Passepartout gets drunks on vodka and can’t spell Novorossiysk; and the journal keeps trying alternatives and deleting them, which was an effect that just fell out of the way we were happening to handle the text UI.

The list of things that didn’t work is much, much longer: every game we release is full of compromises - places where I hope the player can’t tell that what I hoped a scene might turn into is quite different than what it actually was. A lot of those are action sequences; action doesn’t leave much room for player failure - so while you can conceive “Passepartout scales the balloon to patch the air leak," making that interactive doesn’t pan out so well since he can hardly be allowed to fall off. My chapter of Over the Alps has a car chase which seemed like such a good idea until I was trying to write choices to pace out the narrative and I had nothing: er, steer efficiently and drive fast, please?

My solution to action set-pieces, by the way, is almost always to have a secondary character, so the player can be busy arguing with someone while the action happens as it must!

Alex: Many of your games deliver narrative non-linearly; the player can access narrative chunks in different orders. Do you write differently for non-linear narrative? What does that give the player that a linear narrative can’t?

Jon: For me the most important thing is narrative momentum. I hate that thing in games where you’re wandering around aimless waiting to hit the next checkpoint to kick the next bit of narrative along. I want the story to be constantly spooling out - even if that’s the characters walking in silence because that’s appropriate.

And you simply can’t get that effect if the narrative is linearly delivered - or even if the narrative is non-linearly delivered, but non-contextual. (To give an example of that, I loved the Outer Wilds, but I didn’t like its narrative stuff very much because I would do some hair-raising gameplay, then meet a character and have a really sedate chat with them. The lore and content was interesting, but the delivery was only “pick things up”.)

I want the narrative to envelop and evolve around me, and in any game that isn’t a branching 80 Days-style flow, that means in my experience that the narrative has to be built from opportunities and guards. We write a script full of narrative moments, guarded by the conditions that make them make sense; and some of those moments are opportunities that create narrative moments later down the line, and we push those onto the player when the game thinks they’re running dry.

(So for instance, in Heaven’s Vault, Huang the librarian has a story he can tell the player about a trader on the market moon of Renaki. He’ll only tell it to you if you’re nice to him - but also, only if the game thinks you need it.)

But that design means that there’s very little control over what order things happen in - in Pendragon, when characters encounter a scene, we never know who's in the party, how many people are there, how healthy they are - so we try to cover all those possibilities with a strategy of sensible defaults and specific overrides. Everyone will have *something* to say, but if you’re there with Merlyn, you’ll get this particular insight.

It’s all about having a good authoring system; once you have you have your content pattern worked out, this kind of structure is very easy to throw content into because you don’t need to think about the flow of the scene at all, and there’s no limit to how much you can throw it because all of it turns up sometime, for someone.

The flip side is that it does limit your ambitions: a scene which would require too much specific writing to handle being told out of sequence simply can’t go in the game. But writing within constraints is… normal?

Alex: Is there academic theory that you find useful in your game writing? What did you learn from it?

Jon: I tend to pick up theories and advice quite impressionistically: a tidbit here, an idea there; things I hear from clever people that resonate with my experience of writing. I’ve never seen any holistic theories I can get behind; they’re usually too simple, and they never seem to resonate: they often feel like people theorising in a vacuum rather than describing how they work.

The most significant things I picked up were ideas floated by the interactive fiction community in the early 2000s, where we used to make really ambitious text-based games that explored wonderful ideas, like the separation of the player and protagonist (with unreliable narrators, and games that lied to you, and games built on dramatic irony). And I attended a 4 day Robert McKee “Story” course, which I detested, but came away from with a huge number of useful ideas. (I think many of them are actually Aristotle’s, not McKee’s; and many are just ideas - not rules - but I can’t deny I was challenged and stretched by the course.)

But one thing I’ve noticed is that the most useful tools to me are all really lenses for working out why things aren’t working, rather than ideas for how things Should Go.

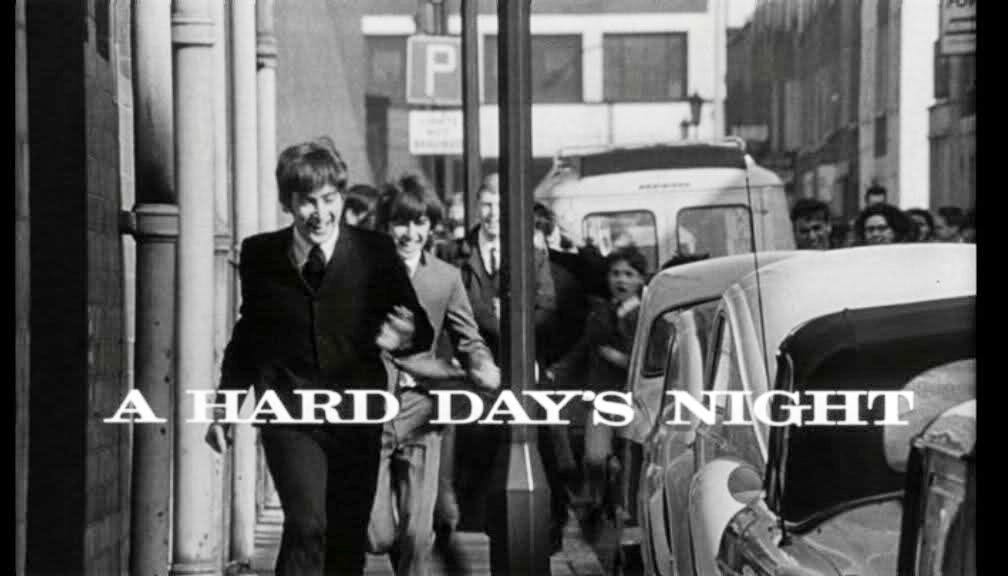

Alex: I think that’s a really good point. There are all sorts of games and films that seem to break the rules and work anyway. What’s the three-act structure of A Hard Day’s Night? When something works, you don’t need the rules. You need them when it doesn’t work.

Which are the games that inspired you? And did they work?

Jon: Spider & Web - a spy story, told in flashback during an interrogation. Every time you fail a timed puzzle, the interrogator insists that you’re lying and makes you tell the story again. As you fail, you slowly learn a few more details about what happened leading up to that point, culminating in a moment of pure insight which allows you to escape. It’s a bit like the device Prince of Persia used, only tied directly into the core game mechanic.

9:05 - a short game in which you get up and go to work, and then it turns out you weren’t who you thought you were, and you replay the game and realise you just assumed you were, but you weren’t.

Galatea - a short game in which you talk to someone, and that’s all you do, but they slowly change their attitude to you based on what you say.

Rameses - a game about an introvert teen, who refuses to do most of the things you ask him to because he’s too introverted. Has a great twist when you think you know how the story is going, because it’s that kind of story, but then he’s too shy to do that too.

Shrapnel - a game that occasionally types in commands for you regardless of what you type, because destiny

The Gostak - a game that’s written in a language that isn’t English, which you have to figure out as you play

The Edifice - a game where you have to learn an alien language to communicate with another character

Photopia - a game about a tragic, needless death, where nothing you do can change anything, told out of sequence for maximum impact

… honestly, it was a melting point of brilliant ideas, and within the constraints of being parser games they were well-implemented too.

Alex: What do you do to stay sane?

Jon: I don’t stay sane very well, I think; I tend to get over-excited mid-project and then heart-broken post-project, and then pick myself up by doing another project and repeating the whole cycle… luckily, though, I have small children, who are extremely diverting and distracting and ground me in a little in something more closely resembling reality.

Sometimes I manage to read books, too - mostly Agatha Christie, Ursula Le Guin or Gene Wolfe - though I find my concentration span is rather feeble these days. And my wife and I watch dramas on TV but only if they have jokes and no torture, which rules out 99% of shows.